Hill and Hollow Original Readings in Appalachian Women's Studied

Overview

Launched in 1964, the State of war on Poverty speedily entered the coalfields of southern Appalachia, finding unexpected allies among working-course white women in a tradition of citizen caregiving who were seasoned past decades of activism and customs service. In To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2019), Jessica Wilkerson tells how these women acted as leaders—shaping and sustaining programs, engaging in ideological debates, offer fresh visions of democratic participation, and facing personal political struggles. Their insistence that caregiving was valuable labor clashed with entrenched attitudes and rising criticisms of welfare. Their persistence brought them into coalitions fighting for poor people'due south and women's rights, healthcare, and unionization. The following essay is adjusted from the epilogue of Wilkerson's volume.

Weblog Post

The activism of Appalachian women who took upwards the fight for justice in the 1960s and 1970s pulsed outward from a core ethic of care. Caregiving animated their understanding of politics and activism and infused their movements. one Berenice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto, "Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring" in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives, eds. Emily Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (Albany: Land University of New York Press, 1990), xl. Historically, Appalachian women had tended to the broken bodies of miners and industrial workers, mourned the dead, raised children, and negotiated a subsistence economy. They did so not because women are inherently more than nurturing than men but because civilisation, society, and law carved out these positions. Most caregivers exercise non become activists. The merging of an ethic of care with democratic struggle provided a powerful argument that caring is central to the fight for justice, fairness, rights, and republic. Women drew upon their experiences in shaping movements for labor and welfare rights, ecology justice, access to healthcare, and women's rights.

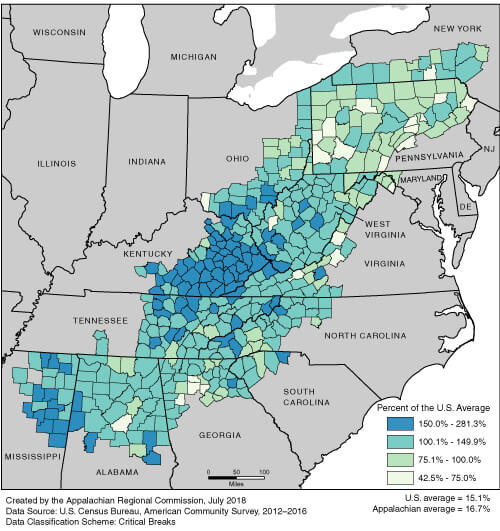

In the last thirty years, working-class caregivers have faced a United states political economy ever more hostile to their needs and concerns and increasingly demanding of their fourth dimension and energy. Although overall poverty has decreased since the 1960s, many locations in the Appalachian South, like rural and working-class communities across the nation, have experienced the rise of farthermost economic inequality, and a growing separate between rural and metropolitan residents. 2 See Ronald D. Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945 (Lexington: University Printing of Kentucky, 2008), 232–233. In the Appalachian coalfields, the last decades of the twentieth century ushered in the terminal and almost sharp decline of that industry. Although mine owners and operators had long exploited workers, mining was for many years the best paying work around. When those jobs disappeared, no other manufacture filled the gap and more people entered the low-wage service economy, surviving with picayune in the way of workplace benefits or economic security.

Relative Poverty Rates in Appalachia, 2012–2016 (County Rates equally a Percentage of the US Average), July 2018. Map by the Appalachian Regional Commission. Courtesy of the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The loss of mining jobs and the transition to a global marketplace and service economy paralleled the unraveling of the social safety net. In the 1990s, the bipartisan dismantling of Aid to Families with Dependent Children left poor families, and in particular women, on shaky basis and delivered a severe accident to decades of activism to guarantee welfare rights. three Deborah Thorne, Ann Tickamyer, and Mark Thorne, "Poverty and Income in Appalachia," Journal of Appalachian Studies 10, no. iii (2004): 341–357. See also Debra A. Henderson and Ann R. Tickamyer, "Lost in Appalachia: The Unexpected Impact of Welfare Reform on Older Women in Rural Communities," Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 35, no. three (2008): 153–171. Wellness clinics, legal aid services, and local organizations—the legacies of 1960s activism—stood as the simply buffers in a political economy increasingly hostile to poor and working people.

In the popular imagination, "Appalachia" functions equally shorthand for a white working class—coded equally male industrial workers. For months before and afterwards the 2016 election, journalists reported on various Trump Countries, every bit they were dubbed—Appalachian communities supposedly serving equally ground zero for understanding working-class support for a billionaire who claimed to care most the "forgotten people" of America. This signposting immune for an evasion of any deep assay of racism or growing economic disparity, generations in the making and never contained to ane region. iv Roger Cohen, "We Need 'Somebody Spectacular': Views from Trump Country," The New York Times, September 9, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/xi/stance/sunday/nosotros-need-somebody-spectacular-views-from-trump-state.html; John Saward, "Welcome to Trump County, The states," Vanity Fair, February 24, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/02/donald-trump-supporters-west-virginia; Larissa MacFarquhar, "In the Heart of Trump Country," The New Yorker, October ten, 2016, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/mag/2016/10/10/in-the-heart-of-trump-state. For a full list and analysis of this coverage see Elizabeth Catte, "There is No Neutral There: Appalachia every bit Mythic 'Trump Country,'" October 16, 2016, https://elizabethcatte.com/2016/10/16/appalachia-every bit-trump-country/.

Such portraits rely on exhausted tropes that erase the voices and experiences of working-class women, a multi-racial and -ethnic grouping, from history while wiping from historical memory the progressive activism long central to Appalachia's history. Such a narrative ignores the experiences of the vast majority of the region's workers (many of them women) who are not employed in heavy industry, but in the work of caring: health care support, teaching, and social services.

Conceptions of "workers" that exclude and marginalize caregiving, or bandage Appalachia every bit an isolated, out-of-pace place, accept little adventure of generating the kind of various, hopeful coalitional work that emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Women activists in Appalachia and their allies—civil rights activists, lawyers, doctors, spousal relationship organizers, feminists, and students—worked for what they believed was possible: the common good in their communities, region, and nation. Their most potent tool was the knowledge that they carried from a lifetime of tending to families, surviving tragedies, bearing witness to the disasters of unregulated capitalism, advocating for their communities, and taking stands for fairness and justice. Their stories are tools for the present, charting a path to a lodge that centers and values life-sustaining labor.

Virtually the Author

Jessica Wilkerson is assistant professor of history and southern studies at the University of Mississippi.

Embrace Epitome Attribution:

West Virginia Teachers' Strike, Charleston, West Virginia, March ii, 2018. Photograph by Emily Hilliard. Courtesy of the West Virginia Folklife Plan at the West Virginia Humanities Council.

Recommended Resources

Text

Carawan, Guy, and Candie Carawan, eds. Voices from the Mountains: Life and Struggle in the Appalachian S—The Words, the Faces, the Songs, the Memories of the People Who Live It. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.

Catte, Elizabeth. What Y'all Are Getting Incorrect About Appalachia. Cleveland, OH: Belt Publishing, 2018.

Eller, Ronald D. Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

Engelhardt, Elizabeth S. D., ed. Beyond Colina and Hollow: Original Readings in Appalachian Women'southward Studies. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005.

Fraser, Nancy. "Contradictions of Capital and Intendance." New Left Review 100 (2016): 99–117.

Lewis, Helen M. Helen Matthews Lewis: Living Social Justice in Appalachia. Edited by Patricia D. Beaver and Judith Jennings. Lexington: Academy Press of Kentucky, 2012.

Maggard, Sally Ward. "'We're Fighting Millionaires!': The Disharmonism of Gender and Class in Appalachian Women's Union Organizing." In No Middle Ground: Women and Radical Protest, edited by Kathleen One thousand. Blee, 289–306. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Moore, Marat. Women in the Mines: Stories of Life and Work. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1996.

Rice, Connie Park, and Marie Tedesco, eds. Women of the Mount South: Identity, Work, and Activism. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Seitz, Virginia Rinaldo. Women, Development, and Communities for Empowerment in Appalachia. Albany: Land University of New York Press, 1995.

Spider web

Achten, Ellee. "In Appalachia, Women Put Their Bodies on the Line for the Country." Rewire News, Baronial three, 2018. https://rewire.news/article/2018/08/03/in-appalachia-women-put-their-bodies-on-the-line-for-the-land/.

Appalachia: Family and Gender in the Coal Community Oral History Projection. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries (Lexington, Kentucky). Accessed March 8, 2019. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt773n20g49j.

"Appalshop." Appalshop, Inc. Accessed Feb 7, 2019. world wide web.appalshop.org/.

Catte, Elizabeth."Finding the Futurity in Radical Rural America." Boston Review, January 26, 2019. http://bostonreview.internet/politics/elizabeth-catte-finding-future-radical-rural-america.

Cheves, John, and Pecker Estep. "Chapter seven: Bombs and Bullets in Clear Creek." Lexington Herald Leader, terminal modified Baronial 29, 2018. https://www.kentucky.com/news/special-reports/50-years-of-night/article44430654.html.

Lewis, Anne. Evelyn Williams. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1995. https://www.appalshop.org/media/evelyn-williams/.

———. Fast Food Women. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1991. https://www.appalshop.org/shop/appalshop-films/fast-food-women/.

———. Mud Creek Clinic. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1986. https://www.appalshop.org/shop/appalshop-films/mud-creek-clinic/.

Phenix, Lucy Massie. You lot Got to Move: Stories of Alter in the Southward. Harrington Park, NJ: Milestone Moving-picture show & Video, April 17, 2015. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/36437/125290704.

Stine, Ali, and Cynthia Greenlee. "The Year in Appalachia: What Happened in 2018." Rewire News, Dec 19, 2018. https://rewire.news/article/2018/12/nineteen/2018-appalachia/.

Similar Publications

Source: https://southernspaces.org/2019/you-cant-eat-coal-and-other-lessons-appalachian-womens-history/

0 Response to "Hill and Hollow Original Readings in Appalachian Women's Studied"

Post a Comment